KERAMIK CONVERSATIONS

from Vallauris to Fat Lava

Perspectives on Post-War, Popular Ceramics from Germany and France

The Ceramics Gallery at Aberystwyth Arts Centre:

4 May - 22 September 2013

|

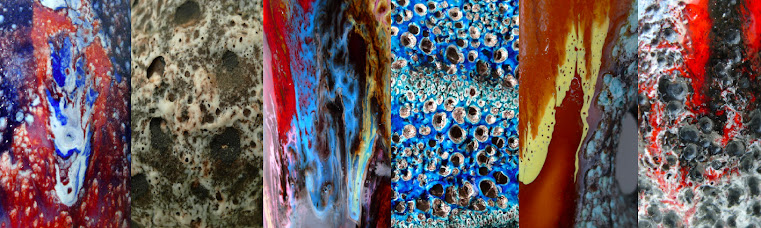

| Left: Marino Le Vaucour, Vallauris (1960s) . Right: Marei Keramik (1970s) |

Note that a more comprehensive, on-line resource about German, Vallauris, Annecy and British ceramics of that period is also available at: http://ceramicsconversations.blogspot.co.uk/

Double click on images to enlarge.

A number of links to videos have been included.

Comments and complements of information welcome!

INTRODUCTION

The exhibition presents a selection of STUDIO and FACTORY-produced ceramics; made in FRANCE and GERMANY during the 50s, 60s and 1970s, in a democratic move to take MODERNITY into every home, through ceramics.

In Germany this democratic move was inspired by the BAUHAUS.

In France the development of a playful popular modernity was influenced by the coming of PICASSO and by the arrival of fine artists and art-school-trained ceramicists who moved to Vallauris to reinvent themselves as 'artist-potters'.

This influx of newcomers inspired traditional potters like Joseph Calvas-Blanchon, Jean Rossignol, the Foucard-Jourdan family, Joseph Saltalamacchia and others to shift from the production of the traditional — and now obsolete — cooking pots [traditionally made in fragile, low fired earthenware, simply glazed in yellow or green] that they had been making for centuries], to the making of decorative wares for the tourist market. Initially adapting the same materials and techniques of 'terres vernissées' [see case 8], then gradually switched to new industrially produced bright glazes; such as 'écume de mer'.

The transition did not happened overnight, but took place within the space of a decade: from around 1950 to 1960.

The exhibition focuses on the development of experimental glazes — 'ECUME DE MER' in VALLAURIS, 'ÉMAUX DES GLACIERS, ÉMAUX DES NEIGES' in ANNECY, ` LAVA' glazes in GERMANY, which complemented painted figurative or abstract geometric motifs with rich COLORS and TEXTURES, and radically transformed the MATERIALITY of ceramics.

Alongside these more experimental glazes, the same workshops and factories continued to decorate their wares with hand-painted figurative motifs (both traditional and modern); often on the same vases that were decorated with lava glazes. This is particularly noticeable in the works produced by Marei Keramik (See forthcoming book on Marei by Ralf Schumann, 2014)

KERAMIK CONVERSATIONS traces the emergence and spread of a new popular ceramic modernity, which, with its radical new glazes, provided an URBAN alternative to the neo-traditionalist,ruralist-revivalist aesthetics of the 'brown pots brigade'.

PRECEDENTS: These post-war developments were paved by the discovery by Europeans (from the 1870s onward) of Japanese stoneware vessels for the tea ceremony, and by the color experiments conducted by Pierre Adrien Dalpayrat and others, during the 1890s. These capitalised on recent developments in glaze chemistry and kiln technologies:

|

Dalpayrat, Vallauris, Annecy, Germany… |

CHEMISTRY INTO ART OR ART INTO CHEMISTRY?

In his excellent article, Crags and Crevices (ceramic Review, nº 239 S/O 2009 Mike Bayley describes different ways of producing 'lava' (which he calls 'eruptive') glazes.

The easiest and most widespread involved adding silicon carbide to a conventional glaze to produce blisters all over the surface of the pot. An other way involves double dipping in glazes of different properties (different reactivity to temperature) — like an earthenware glaze under a stoneware glaze — to produce contractions, bubbles, occlusions, runs, etc.

Calling the potters who produced these works 'glaze chemists', as Paul Rice and others (after Bernard Leach) have done, is problematic; for it dismisses the works on the assumption that bright textured glazes represent a corruption of 'good (ceramic) taste'.

CRAFTS INTO INDUSTRY

Keramik Conversations challenges the arbitrary boundaries erected between CRAFT and INDUSTRY — by the Arts and Craft Mouvement, and consolidated by the pottery revival instigated by Bernard Leach, from the 1920s onward — and explores how craft skills, used in studio and in industrial (or semi-industrial) conditions, generated discrete CERAMIC MATERIALITIES, with their own legitimate aesthetic values.

This was the result of a deliberate move to create a new ceramic modernity and make it available to a larger public.

These works have, so far, eluded the attention and interest of museums and museum curators, and their recent re-discovery (still in progress) has been, and remains, the work of enthusiastic private collectors.

Although 'Vallauris' and 'Fat Lava' collections have been showcased in isolation from other ceramic strands (one exhibition titled 'From Sgrafo to Fata Lava'), presenting individual collections in rather straight-forward encyclopedic ways, this exhibition sets these experiments with lava glazes, critically and historically, in the context of an expanded ceramic history.

'CONVERSATIONS…'

METHODOLOGY: The exhibition stages conversations between ceramic objects: to explore their individual materialities, free from aesthetic hierarchies, divisive categories and period boundaries.

Acknowledging, after Barthes, that (ceramic) meanings are not in the object itself — given once and for all (as museum displays tend to suggest) — but arise from the interaction between an object and the person/s who view it (and from the interaction between objects) — the exhibition aims to open up the ceramic field and define new ways of approaching ceramics; not in isolation but relationally; free from conventional assumptions: on an expanded, inclusive (non-elitist), aesthetic basis.

The juxtapposition in one display case (below), between a 'classical' eighteenth century Blanc de Chine porcelain vase (built according the principle of symmetry along a vertical axis) and an experimental hand-built 'forme libre' [free form] stoneware vase (built on the principle of assymmetry), from Atelier Giraud, in Vallauris, invites us to engage these two items in their respective formal, cultural and aesthetic qualities, and to appreciate their contrasting 'materialities' — and their significance — relationally (not in isolation from each other), by re-positioning them in an expanded (deregulated) ceramic history:

SIGNIFICANT PRECEDENTS

The exhibition includes a few earlier experiments with color in order to put the post war works in context: from Dalpayrat's luscious glaze experiments carried out during the 1890s to the experiments with crystallisations at Grès de Pierrefonds (France); the systematic exploration of color glazes at Royal Lancastrian (Britain) [case 6]; the stoneware revival in Puisaye (instigated by Jean Carriès and expanded by his 'School', in response to Japanese stoneware) [with an example by Léon Pointu, son of Jean] (case 7)]; a 17th century Japanese stoneware bowl for the tea ceremony and a vase by the second exponent of the Shinsui (Tamba) kiln: Ichino Shinsui [case 13]; and, finally, the Bauhaus, which, by advocating the integration of crafts, design and industrial processes, defined a new ceramic Modernity; affordable, potentially, to every home, according to the principles of a new democratic aesthetic. [case 3 & 12]

An earlier piece by Léon Marc Castel (son of Léon Castel), produced at his Poterie du Mont Chevalier, in Cannes, soon after 1902, represents an early, and isolated, attempt at producing a volcanic glaze.

KERAMIK CONVERSATIONS

START FROM THE OUTSIDE (moving from left to right; viewing from the lobby)

|

| Setting up, June 2013. |

The exhibition is constructed as a POLYLOGUE (a discourse of many voices) and starts from the lobby, where a number of displays (like a façade or frontispiece) set the tone; introducing the exhibition thematically: 1. Mythical Origins of Ceramics. 2. Vallauris: the Reinvention of Tradition. 3. Experimental glazes in France and Germany. 4. Bauhaus: from Geometric to Organic. 5. Schäffenaecker: Redefining the vase as sculpture. 6. Anti-glazes: Le Cyclope. (Annecy). 7. Studio vs Industrial…

Display case 1

above

above

1-2. The (mythical) origin of

pottery:

It has been suggested (by anthropologists and by archaeologists) that pottery was 'invented' — or 'discovered' — by chance; when a woven basket, coated with clay on the inside (to hold water), was inadvertently left near a fire and burnt slowly; leaving a fragile clay skin standing in its place, with the pattern of the basket impressed in the clay.

This story is also used to explain the traces of decorative basket patterns imprinted on early pottery.

We will never know the truth, but can consider the story as a plausible, credible, poetic hypothesis.

Although the thin crust of baked clay could not have been functional, without the supporting structure of the basket [too fragile to hold water], it may have inspired someone with foresight to pursue the experiment till the 'shell' became a 'vessel' strong enough to hold water.

This first 'conversation' in the exhibition takes this story as its starting point, looking at formal analogies and functional differences between STRUCTURE and DECORATION: between the structural pattern of a woven basket [and its decorative potential] and the complex decorative pattern of indentations and scarifications meticulously cut/imprinted into the surface of a stoneware vase, by Heiner Hans Körting, when the clay was still wet:

| |

|

'Hand-writing': Traces of the process: On closer examination [click on the image below], we see how the clay lifted under the pressure of the cutting tools (leaving a raised rim), and how part of the cream slip ('engobe') flaked off as each identation was made and each piece of clay was cut off and lifted from its place; leaving a raw edge and exposing the color of the clay underneath :

In the vase, however, some irregularities do occur — subtle and almost imperceptible — in the micro variations between each of the maker's marks: through the dizzying repetition of pressing the tool, cutting and removing bits of clay: to create as regular and as complex a pattern as could be achieved by virtuoso human hands; leaving the distinctive mark of the potter's 'hand-writing' through its just less than perfect geometry.

Taking a considerable amount of time and care — more than was necessary (but who is to say what is necessary in this case, without running the risk of imposing dogmas, such as 'Ornament is crime' ?) — and applying a high level of art (in the design) and craft skills (in the execution), in order to produce a richer and more complex pattern, highlights one feature of the 'aesthetic' dimension.

unlike in the Chinese bamboo charcoal basket ('Sumikago'), used in Japan for the tea ceremony, where the decorative effect is produced exclusively by the woven structure itself…

below

3-4. The reinterpretation of Tradition:

Set up in 1920, in Biot, by René Augé-Laribé, La Poterie Provençale specialised in the making of vessels in the tradition of 'Terres Vernissées', adapting them from their recently made obsolete storage function (water, oil, wine) to that of garden ornaments. He also produced smaller decrative items, for the home, like this hand-thrown amphora-shaped earthenware vase. Today the grandson René Augé-Laribé continues the family tradition in Biot.

La Terre en Forme, an off-shoot of the family firm was set up in 2010, by one of René Augé-Laribé's descendants, in Forcalquier. It still uses the traditional technique of ropes and wheel to make very large 'jarres'.

By contrast, the slipcast earthenware vase (above right), by an unidentified maker reinterprets the pilgrim jug in a modern version of the Baroque, with echoes Jean Cocteau's surrealist interpretation of Classicism.

Above

5-6. Marino Le Vaucour. (Vallauris). Free form

vase. Slipcast earthenware decorated with 'Écume de mer' glaze, 1950-60 . Marei Keramik (Germany). Vase. Slipcast stoneware, decorated with thick orange lava glaze over matt pumice glaze. Late 60s or early 70s.

The 'bubbly' 'écume de mer' glaze on the Vallauris sculptural slipcast free form earthenware vase (left) and the 'luscious' orange-red 'lava' glaze on the Marei Keramik moulded stoneware vase embody two remarkable contributions to the new, popular ceramic modernity that arose in France and Germany during the postwar years.

These industrially-produced forms achieved an unprecedented experimental aesthetic quality, through the integration of art, craft and design skills as part of an industrial making process.

Whereas we know, from Abraham Lomax' s book Royal Lancastrian Pottery 1900-1938 (Bolton, 1957) the names of the individuals who made and glazed the Royal Lancastrian vases (as well as the 'artists' who decorated them), the names of the authors (the chemists and the glaziers) of the spectacular orange-red glaze on the right — and of most (if not all) LAVA glazes produced in Germany — seem to have been lost. In some cases we know the name of the designer.

The exhibition pays tribute to the these forgotten [and unrecognized] 'creators' who played an important part in fostering this new modernity…

The exhibition pays tribute to the these forgotten [and unrecognized] 'creators' who played an important part in fostering this new modernity…

7-9. Scheurich, 3 vases (244/17).

Form (1959). Glaze (1970s).

Scheurich is one of several manufacturers who produced 'lava' glazes. The practice of decorating the same form (above: form 244 in size 17 cm) with different glazes enabled German manufacturers to extend their range at lower costs, and enabled amateurs to collect and make arrangements with vases of the same form, in different colors; a practice widespread today among collectors of West German 'Fat Lava'.

The soft and fluid contraction of the glaze in these and on the larger iridescent purple vase (517/30), in display case 15, are characteristic of this manufacturer, and are easily recognizable (on close inspection) from lava glazes produced by Fohr, Jopeko (many of which have now been re-attributed to Stein), Marei and Roth Keramik, that can be seen in the exhibition.

|

| From Left to right: Scheurich, Fohr, [Jopeko]/Stein (red), Jopeko/Stein (white), 1970s. |

The chemistry of lava glazes…

Clockwise: Scheurich (yellow), Jopeko/Stein (red), Fohr (red), Jopeko? (white).

Clockwise: Scheurich (yellow), Jopeko/Stein (red), Fohr (red), Jopeko? (white).

(to be developed)

See Mike Bayley' s informed, technical article about lava glazes, 'Crags and Crevices' ( Ceramic Review, nº 239 Sept/Oct. 2009), pp. 64-67.

In addition to early Japanese experiments, one should mention Lucie Rie, who produced some 'lava'-type glazes as early as 1936-37, in Vienna. These are strangely reminiscent of one of Scheurich's industrially produced glaze, as can be seen in the lidded pot (below), in the V & A museum :

Similar glazes were also produced by Walter Gebauer in the late 60s.

(see Walter Gebauer ein Töpfer aus Bürgel, 1998, p. 56). Earlier during the 1920s, Jackson Pollock-like glazes were produced by Louis Dage in Paris and by Céramique La Charentaise, at Angoulême (see 28-28, below)

[Entrance Door] Continue on the outside to display cases 3 & 4:

Display case 3

Above

10-11. Margarethenhöhe Keramische

Werkstatt. Left: Johannes Leßmann, 1930s. Right: Walburga Külz, late 40s/early 50s.

A shift from geometry to organic simplicity and unity of form took place around 1950, under the influence of 'streamlining'.

This shift can be observed by comparring two works from Margarethenhöhe Keramische Werkstatt: a jug in Bauhaus style, by Johannes Leßmann from the 1930s, and a more fluid vase by Walburga Külz, from the late 40s or early 1950s, reminiscent of ancient ritual vessels found in archaeological museums:

It can also be observed in two works by Walter Gebauer, from 1938 and 1951, respectively, displayed in the virtual gallery:

and in three jug-vases ('krug' vases) by Ursula Fesca, produced for Wächtersbacher during the 1950s [display case 12 ]

Stylistically close to the Bauhaus, the one on the right may have been originally designed during the 30s, during Fesca's first period of employment at Wächtersbacher (before illness forced her to retire); and could have been 'produced' and edited sometimes during the early 1950s, when she came back as artistic director. The body of the vase is heavier than that of the two others in the display, both made during the 50s.

The red vase, of the same earlier design, however, is much lighter, like the one on the left.

Below

12. Helmut Schäffenacker, Triple

vase. c. 1950s.

During the 1950s, German sculptor Helmut Schäffenacker began to experiment with ceramics; first making ceramic plaques; a popular equivalent of modern art/painting for the home:

Subsequently, he produced vases, which he treated as sculptures.

Some are geometric in form, others are organic, like this triple vase (below), which he produced in many variations of form, size and glazes. All make a reference to the mineral world; both in their forms and in their glazes.

|

| Decorative plaque in neo-Cubist style, 1950s. |

Subsequently, he produced vases, which he treated as sculptures.

Some are geometric in form, others are organic, like this triple vase (below), which he produced in many variations of form, size and glazes. All make a reference to the mineral world; both in their forms and in their glazes.

[A small monochrome version from the same series is displayed 'in conversation' with works by Hans Copper and Lucie Rie, in the permanent collection (See blog section 4, n. 1)

His amonite vase, can be seen in the permanent collection, in dialogue with a large mineral composition by Ewen Henderson, as part of a dynamic display conceived as a ceramic procession/cavalcade, from right to left. Sec tion 4, n. 26]

Schäffenacker made his moulds and cast his vases himself; and only employed a small number of assistants for applying the glazes.

In pieces like this, however, he applied the glazes himself, provoking and capitalising on accidental runs and overlays, leaving some parts unglazed; working in a way not dissimilar to that of an abstract painter.

Display case 4

13-14. Left: Ruscha. Vase 333. 1970s [Forrest Poston informs me that form number '333' was first used by Ruscha in 1958 (for a smaller vase of totally different design), and re-used for this larger vase, during the 1970s. This brings the two vases closer in date] . Slip cast stoneware. Hans Siery (form), Otto Gerhaz (glaze). Right: Schäffenacker. Vase V13. c. 1960. Slip cast stoneware.

The perfect line and smooth finish of the slipcast Ruscha 'Krug-vase' (left) — reminiscent, in its form, of ancient ritual vessels displayed in archaeological museums — contrast with the heavy, irregularly shaped and textured stoneware vase by Schäffenacker, decorated with a matt green and brown glaze. Although both were cast from a mould, mould casting technology here serves different aesthetics, and the works can in no way be described as 'the work of machines', as the studio pottery 'fundamentalists' would argue.

Comparing these two vases — in their forms and glazes — with the hand-thrown stoneware vase from La Poterie de la Montagne (St Honoré), in case 6 [inside the gallery], we note a similarity in colors in the St Honoré and the Schäffenacker matt glazes, but also their extreme difference in form (symmetry/assymetry) and aesthetics (tradition/modernity).

Below

15. Charles Cart. 'Le Cyclope' pottery (Annecy, France). Soup terrine. Slip-cast earthenware, decorated with ‘Émaux des

glaciers’ glaze. Late 50s/early 60s. (Cart developed this glaze after asking chemists to show him how to ‘spoil’

glazes).

The bursting of bubbles in the multi-layered, magma-like, runny glaze reveals a richness and lusciousness of color and textures; with an added irreverent, dadaistic sense of play which, today, given the conventionalism and one-dimensionality of popular decorative ceramics, confer upon it the quality of a Post-Modern fine art intervention.

Cart used bought-in blanks for this item; for his small pottery was not equipped or staffed to slip-cast on a large-scale. His vases, however, tended to be hand-thrown. For this and similar items, it was cheaper to buy-in blanks and decorate them in house.

This practice was also widespread in Vallauris, where the industrial makers of now obsolete cooking pots sold them to different factories to be decorated with bright colors, which gave them a new lease of life as ornaments.

Cart used bought-in blanks for this item; for his small pottery was not equipped or staffed to slip-cast on a large-scale. His vases, however, tended to be hand-thrown. For this and similar items, it was cheaper to buy-in blanks and decorate them in house.

This practice was also widespread in Vallauris, where the industrial makers of now obsolete cooking pots sold them to different factories to be decorated with bright colors, which gave them a new lease of life as ornaments.

Display case 5

16-17. Pol Chambost (France). Vase. Hand-thrown and carved earthenware (1930s-50s?) . Irene Pasinski (USA), vase 605/2. Slipcast stoneware for Gräflich Ortenburg (1958).

The perfect line of the Chambost may lead one to assume that it was slip-cast and that the Pasinski, with its rougher texture, was hand-thrown. On closer inspection, however, it appears that the sgraffitoed pattern on the neck of the Chambost (left) are irregular and more clearly the result of hand carving rather than of moulding. This is confirmed by looking inside the vase to see the concentric signs of hand-throwing.

Whereas the smooth glaze on the Chambost vase recalls the smooth sang de boeuf glazes of classical Chinese porcelain, the glaze on the Pasinski vase deliberately disrupts the surface of the vase with unevenly distributed black occlusions which rise through the textured layer of red.

Remarks: Although hand-throwing can add to the aesthetic quality of a pot, it is no guarantee of quality. Slipcast or press-moulded works can equally achieve aesthetic quality — albeit through a different materiality; often thanks to the properties and qualities, and primary role of the glaze.

In some cases (as in the Marei vases in display case 17), the moulded or slip-cast pot is functioning like a shaped canvas.

By contrast, in vase 333 by Ruscha (see above 13) — the design of the form is more than a pretext for showing off glazes, and contributes significantly to the overall aesthetic of the pot.*

* In this respect, it may be relevant to speak of form-led and glaze-led ceramics when looking at and discussing these works.

Only visible from inside (turn right as you enter the gallery):

18-19. Conversations: Gerda Heuckeroth. Two versions of vase C 236/20, for Cartens Atelier series. Decorated with

a textured red on matt black and a runny black on copper lustre glazes (1962-64).

By making their glazes richer and thicker, and the surfaces of their ceramics more varied and painterly — allowing under-layers to show through color layers — both Pasinski and Heuckeroth paved the way for the development and appreciation of lava glazes.

20. Le Cyclope

(Annecy), large hand-thrown earthenware vase decorated with ‘Émaux des

guarrigues’ yellow glaze.

above

21-23. Pierre Adrien Dalpayrat, 3

vases. Stoneware. (1 & 2 , top left), decorated with copper oxide glazes, with reduction

firing. c. 1895.

For Dalpayrat and his contemporaries the challenge consisted in producing and controlling the chemical reactions of copper oxides mixed with catalysts to achieve several colors in the same glaze layer; without resorting to over-layering:

The start of the process — from red to blue is visible in the vase above.

In this second vase (below) the spectacular result achieved is more complex (more like fireworks) and more of the type which inspired a critic to compare Dalpayrat's glazes, somewhat prophetically, with 'magma' and the 'flow of volcanic lava'.*

* See the essay by Jean Girel in Horst Makus et alt.'s monograph 'Adrien Dalpayrat 1844-1910' (Arnoldsche, 1998), pp. 179-197 [in French and German].

The third Dalpayrat, from the left, was acquired for the permanent collection.

24-25. Grès de Pierrefonds. Blue flamé handled vase (c. 1912)

and globular vase with blue crystalline glaze (c. 1920). Stoneware.

Whereas the design of the vase on the left is clearly Art Nouveau, the one on the right is more timeless and more generically abstract, and decorated with the rarer and more difficult to achieve crystalline blue glaze.

At Pierrefonds research into crystalline glazes was conducted from the beginning of the 20th century. The second catalogue (1928) advises retailers ('fixed delivery date orders') and potential private buyers that some time may be required before a specific design could be delivered in the full crystalline glaze. The manager advised potential clients who wanted 'full crystallization' to accept it on items of different designs (if in stock), or accept the requested design in another effect (either 'semi crystallized' or 'flamé' glazes), to avoid waiting time.

Prices were determined according to the complexity of the effects (and on the technical difficulties in achieving them in the kiln); on a rising scale: from 'flamés' to 'semi crystalline' and 'full crystallisation'.

Below

26. Léon Marc Castel (Poterie du Mont Chevalier, Cannes, 1902-1920). Vase. Stoneware, decorated with volcanic matt glaze. c. 1910.

This small, artistically ambitious pottery, which continued the work begun by Léon Castel (father of Léon, Marc Castel), who set up the pottery in 1879, and passed it on to his son in 1902), produced some stark volcanic and accomplished crystalline glazes. Following an initial success in Paris, the firm lacked the financial resources to promote itself, and struggled to keep afloat, till it closed in 1920.

27. Poterie de la Montagne. St Honoré (Nièvres, France). Vase, hand-thrown stoneware, decorated with cream, green and brown running glazes. 1926.

This hand-thrown, wood-fired stoneware vase was made in 1926, at the rural 'Poterie de la Montagne', at St Honoré (Nièvres, France). Stylistically, it represents the local tradition upon which the sculptor Jean Carriès consolidated the stoneware revival he instigated at St Amand-en-Puisaye; with its emphasis on hand-throwing and wood firing, and other traditional techniques, and on experimenting with the overlay and on the accidental running of muted green and ochre glazes in preference to the bright colors experimented with by Dalpayrat; which relied on larger teams, more complex chemical knowledge and more sophisticated (and costly) kiln technology.

This aesthetics informed the revival of stoneware at the other important ceramic centre of La Borne (Cher); where over one hundred studio potters are still working today.

The remarkable architecture of the 'Poterie de La Montagne' led to its recent listing as 'Monument Historique'.

Antoine Martin, who threw the vase above, is seen here at work, on his own, in the throwing workshop ('atelier de tournage'). The pots drying in the background shows that the pottery produced the works in batches, in a limited set of designs, whose serial number was sometimes inscribed underneath to facilitate re-ordering.

|

28-29. Céramique La Charentaise (Angoulême, France).

Two stoneware vases decorated with color slip. C. 1920s-30s.

These two vases, from a small factory in Angoulême, decorated in a manner reminiscent of Surrealist automatic drawings or action painting, highlight the coexistence between tradition and experimentation. The white and green glaze slip was applied on a hand-thrown, unglazed, pre fired stoneware body; highlighting the strong contrast between the rough, matt surface of the clay and the glossy (toffee-like) drip; evocative, in retrospect, of Action Painting.

The fact that the decoration pre-dates these artistic movements and developed separately from them highlights the presence, during earlier periods, of aesthetic lines that were rediscovered, later during the 20th century, as part of the development of a new ceramic modernity. The re-evaluation of these pioneering works is important; for it shows tha anticipatory role of popular arts and crafts in the development of new aesthetic forms.

30. Royal Lancastrian. Hand-thrown

earthenware vase (by E.T. Radford), decorated in green luminescent glaze, applied by William Brockbank* (1914-20).

* described by Lomax as 'the principal glaze sprayer', 'for thirty years', with unequalled skills;who 'took a deep interest in his work and rejoiced greatly at his success'; and for whom, 'in his leisure hours, violin playing was his recreation'. Lomax's full description of Brockbank's skills and attitude are significant; for they contradict subsequent characterisations of the producers of factory ceramics as mere 'factory hands'.

* described by Lomax as 'the principal glaze sprayer', 'for thirty years', with unequalled skills;who 'took a deep interest in his work and rejoiced greatly at his success'; and for whom, 'in his leisure hours, violin playing was his recreation'. Lomax's full description of Brockbank's skills and attitude are significant; for they contradict subsequent characterisations of the producers of factory ceramics as mere 'factory hands'.

About William Brockbank, see A. Lomax, o.cit. p.126-7.

It is easy to under-estimate vases like the one above; for their simplicity may be construed as 'ordinary' or mechanical although the vase was actually hand-thrown).

When compared with contemporary German works — either produced at the Donburg Bauhaus ceramic studio or in other studios, in the Bauhaus spirit [see display case 3] during the 1920s and 30s — the subtle shades of colors achieved at the Royal Lancastrian works, by Lomax and his team, makes the works stand out by their subtle chromatic variety and, in this case, by their luminous quality.

Lomax left a detailed account of these experiments (including glaze recipees) in his book 'Royal Lancastrian Pottery: 1900-1938' (Bolton, 1957).

Display case 7

31. Louis Dage. Bowl. Stoneware, decorated with a motif of water, overspilling over a landscape of

drought. c. 1925.

Besides certain analogies with craquelé glazes produced forty years later, by Jopeko and Jasba, the theme of water overspilling from the vase — like a wave — over a landscape of drought takes the decoration of this piece into a conceptual dimension, which contrasts with the more conventional Art Déco and later approaches to surface decoration with floral or geometric motifs, or with abstract craquelées glazes.

In the absence of documentation, we can only speculate about the intentions of Louis Dage in producing this design. What seems certain is that its inspired one of its owners to use it as a planter!

Below

Below

32. Léon Pointu. Vase. Slipcast stoneware, decorated with glossy and matt patches of rust, cream, brown, purple and black glazes.

This example of a work from the 'School of Carriès' shows how the interaction between an artist (Jean Carriès) and a traditional potter (Léon Pointu, son of Jean Pointu), in St Amand in Puisaye, resulted in a revitalisation of the old local stoneware tradition.

Remark: The mass-production by small factories of form and glazes in the Art Nouveau style, in response to the fashion for 'grès flamés', led to the production, well into the 1920s, of formulaic slipcast wares made for the mass market. Eugène Lion and Jean Pointu, however, produced works of integrity (Pointu using slipcasting, as in this example); by experimenting with the color and materiality of their glazes.

Remark: The mass-production by small factories of form and glazes in the Art Nouveau style, in response to the fashion for 'grès flamés', led to the production, well into the 1920s, of formulaic slipcast wares made for the mass market. Eugène Lion and Jean Pointu, however, produced works of integrity (Pointu using slipcasting, as in this example); by experimenting with the color and materiality of their glazes.

33. Atelier Louis Giraud. Vase of sculptural ‘free form’, decorated in matt black textured over brown shiny glaze. c. 1940s-50s:

Early on, as VALLAURIS was making a transition from the production of now obsolete cooking pots to that of decorative wares, Louis Giraud brought a much needed spirit of modernity — with forms reminiscent of Art Déco — but drawing also from an abstract fine art PRIMITIVISM, which confers upon many of his works a sculptural quality (see the 'forme libre' double vase in display case 10).

34-35. Atelier of Jerome Massier. Two vases in ‘forme libre’ (free form). Earthenware decorated with painterly glazes (1950s-60s).

The 'J. Massier' stamp is misleading, for it does not denote the maker, but the name of the firm that produced the designs, over a period of ninety years, under the management of different directors: in this case either Lucien Clergue or Alain Maunier. The vase (above) was acquired by a Belgian holiday-maker, from the J. Massier showroom in Vallauris, in 1969, for his holiday home.

Top

36. Jean Calvas-Blanchon. Vase. Terre

Vernissée (hand-thrown earthenware), c. 1949.

In 1950 Calvas-Blanchon set up FPP (Faïences Poteries de Provence) in partnership with Jean Rossignol; a partnership that lasted till 1967. The firm continued to produce a traditional range of works in 'terres vernissées [for which it was famous, and for which demand remained for decorative items which fueled a sense of nostalgia for a rustic way of life], such as the two pieces below (not in the exhibition):

as well as fruit bowls, jugs, vases, etc.

Responding to changes in popular taste, FPP progressively extended its range by borrowing ideas from fine art.

The pitcher below (in the virtual gallery, not in the exhibition), made by FPP, reads as a 3D interpretation of a Cubist pitcher, inspired by the works of Picasso:

but also adopted some of the gaudy glazes that many factories used, and that became synonymous with (cheap) Vallauris:

37. Foucard-Jourdan. Vase. Hand-thrown earthenware (Terre vernissée). c. 1950s.

37. Foucard-Jourdan. Vase. Hand-thrown earthenware (Terre vernissée). c. 1950s.

This old family of potters was well-known in Vallauris for its domestic wares in 'terres vernissées' (low fired earthenware vessels, glazed in yellow or green): plates, serving dishes, pitchers, large fruit bowls as well as cooking pots .

The vase above was made during the early 50s, and consists of two hand-thrown forms, assembled, the upper part reshaped, and connected with pinched 'collerettes', which both hid and reinforced the connection. It stands as a typical example of Provençal 'terre vernissée': by its style (no nonsense, rustic simplicity) and by the fact it was made using the skills of the two pillars of the traditional pottery workshop: the 'tourneur' (thrower) and the 'hansiste' (handle maker) [see postcard below].

To keep up with fashion and cater for a wider popular tourist market (and boost sales), the firm subsequently produced different versions of this vase; with different painted and scratched flower motifs; below: in the garish style of Poterie de Monaco:

A move that recalls the addition of flowers on Marguerite Friedlaender-Vildehain's Bauhaus modernist Halle vase.

Foucard-Jourdan also introduced 'faux bois', a decor which proved very popular with tourists:

and was copied by other firms to such an extent that it had to be protected by a patent.

This and other stylistic up-datings helped to keep the pottery in production till 1983, under Françoise Jourdan.

This plate, from 1959, by Foucard-Jourdan [not in the exhibition) carries a décor inspired by the pre-historic cave paintings of tassili-n-aijer, in the Algerian Sahara. These and the cave paintings of Lascaux inspired a number of potters and pottery firms from Vallauris and from Germany (Karlsruhe Majolika, Ceramano, among others) who adapted motifs from cave paintings, in response to the rising popularity of Prehistoric Art.

This and other stylistic up-datings helped to keep the pottery in production till 1983, under Françoise Jourdan.

Photo removed due to seller's objection!

This plate, from 1959, by Foucard-Jourdan [not in the exhibition) carries a décor inspired by the pre-historic cave paintings of tassili-n-aijer, in the Algerian Sahara. These and the cave paintings of Lascaux inspired a number of potters and pottery firms from Vallauris and from Germany (Karlsruhe Majolika, Ceramano, among others) who adapted motifs from cave paintings, in response to the rising popularity of Prehistoric Art.

38. Joseph Saltalamacchia. Vase, slip cast earthenware, produced at his Gaby Ceram workshop. Polyhedric vase, decorated with pigments (applied with the spunge), and with sgraffito motifs. Mid 1940s.

This excentric, one-off and very singular attempt — by a traditional country potter experienced in (and well known for) making cooking pots — to develop a ‘modern’ ceramic idiom led to this eccentric vase… an idiolect, that did not capture the public imagination and was never repeated.

In the Vallauris workshops, traditional craft skills, techniques and modes of production continued to be used for the serial production of ceramics for the mass (tourist) market throughout the 50s and 60s.

The photograph (1950s) shows the 'tourneur' (thrower) and the 'hansiste' (handle maker) — two key pillars of the workshop — at work.

Below

39. Marius Mussara. Soliflore vase decorated with Miroesque* abstract motifs on 'écume de mer' glaze.

* Miro was one of the international artists who came to experiment with ceramics in Vallauris. His free use of color in his abstract compositions inspired several potters and workshops (see Panassidi, below).

40. Marius Mussara. Hand-thrown and re-shaped earthenware vase, decorated with black and white lava glaze and red glossy glaze inside. c. 1960.

The strong contrast between the black and white textured (lava) glaze and the smooth red inside of the vase was explored by a number of other ateliers, such as Denys Chiapello, Marius Giuge, Louis Giraud among others.

41. Panassidi. Slip-cast earthenware vase, decorated with single red splash in ecume de mer glaze. 1960s.

Miro's influence is noticeable here, too, in the single, emphatic splash of color…

Double dipping, scrapping an area or using a wax resist process, to allow a patch of glossy red glaze to show through the 'écume de mer' glaze produced this innovative vase, in one of the numerous Vallauris workshops that produced affordable experimental ceramics for the tourist market.

These works are unjustly neglected and derided by the aesthetic snobbery of those for whom Vallauris means Picasso, Capron and the super stars of the auction room.

Double dipping, scrapping an area or using a wax resist process, to allow a patch of glossy red glaze to show through the 'écume de mer' glaze produced this innovative vase, in one of the numerous Vallauris workshops that produced affordable experimental ceramics for the tourist market.

These works are unjustly neglected and derided by the aesthetic snobbery of those for whom Vallauris means Picasso, Capron and the super stars of the auction room.

Display case 9

42. Fady. Hand-thrown tapered earthenware vase, decorated in ‘écume de mer’ over dark blue glaze. 1950s-60s.

The name of the glaze ('écume de mer'; 'froth from/of the sea') is unequivocally illustrated in this hand-thrown vase; with a more luscious, solid materiality than the actual 'écume' from the sea. A careful overlay and dosing of three glazes achieved this delicate balance in their combined flow and mixing, from neck to shoulder…

43. Louis Giraud. Charger. Slip-cast earthenware,

decorated in thick grey and white lava glaze:

[Compare with Marrius Giuge's candelabra in case 11]

This glaze was probably produced by adding a silicon carbide and using twin dipping and partial mixing of glazes to produce the raised lava effect.

44. Michel Ribéro. Thick slip-cast earthenware vase decorated with 'écume de mer' under dark shiny blue glaze (1970s).

The richness and complexity of the glaze (in contrast with many one-dimensional glazes mass-produced in Vallauris) and the heavy weight of the vase confer upon this piece a Sèvres-like quality/nobility/luxuriousness; although it was made for the general public, probably during the 1970s.

45. Auguste Luc(chesi). Vase. 1950s. Slipcast earthenware, decorated in thick, blue 'écume de mer' glaze:

Note how here, as in the vase by Panassidi, the handles merge into the fluid, melting body of the vase. The white clay used to produce these irregular shapes is extremely fragile and brittle, and prone to chipping and breaking; as this one did in the post…

Above

46-47. Anonymous. Blanc de Chine porcelaine

vase (18th century). Atelier Giraud, ‘forme libre’ vase. Hand-thrown, cut and re-assembled, decorated in grey and white lava glaze. c. 1950.

This juxtapposition — which may seem arbitrary at first — is, in fact, intended to conjure up the different parameters which inspired the making of these two very different vases. Two sets of cultural references: to invite us to appreciate their respective formal properties and aesthetic materialities; and to hint at the innumerable possibilities of hybridization available in between.

Close examination of the surface of the vase enables us to see the results of chemical processes in action, which produced its distinctive volcanic or mineral appearance; also evocative of rock formations bearing the marks of wind and water erosion.

49-51. Alexandre Kostanda. Three pitchers. Hand-thrown and cut stoneware, decorated with stoneware slip and clear semi-matt and glossy glazes. (mid 1950s).

Below

52. Alexander Kostanda, Vase.

Hand-thrown, then re-shaped (with some modeling) stoneware. Made whilst ‘chef

d’atelier' at Giraud (1949-53):

Kostanda is credited with introducing stoneware to Vallauris and initiating Daniel de Montmollin to ceramics.

Hand-throwing, combined with the use of natural materials and techniques ('engobe') to decorate the surface of his pots, produces a simple, accessible modernity, which preserves the function of the vase, whilst adding a hint of sculptural quality.

54. Alexander Kostanda, Vase. Hand-thrown, then re-shaped stoneware. Decorated with painted abstract pattern on brown engobe. (1950s):

Here, by contrast, Kostanda painted an abstract (Post-Cubist) composition on a hand-thrown, then pressed, thicker stoneware vase.

55. Marius Giuge. Candle holder (one of a pair)*. Slip

cast earthenware decorated with lava glaze. c. 1960s.

This candle holder was often bought in pairs, with a fruit bowl decorated with the same glaze, to make a spectacular 'dessus de table' display (on dining tables) or on the fashionable scandinavian style side-boards:

56. Attributed to Marino Le Vaucour Moulded earthenware vase, in free form, decorated with ‘écume de mer’ light blue on white over dark shiny blue glaze, on folded and carved body. (1960s).

|

| Slip-cast earthenware vase, in free form decorated with ‘écume de mer’ and red, pink, green and light blue on dark blue glaze. 1960s. |

57. Marino Le Vaucour [attribution based on seeing a vase of the same form, but with a different glaze, signed 'Le Vaucour . Vallauris'. The possibility that two different manufacturers may have bought blanks of the same design remains a (slight, given its extraordinary shape) possibility. This practice is well documented for cooking pots that were produced and sold to different firms, to be glazed decorated with their own designs].

This and the vase above — as well as the large vase in display case 2; all three probably from the same workshop — exemplify the impact of fine art (in the 'free' forms and in the experimental glazes) on an anonymous range of wares (simply signed 'Vallauris') which stand out among the plethora of formulaic vases that have become synonymous with Vallauris and given the town a bad name for kitsch.

Combining, in their spectacular textured glazes, characteristics found in the works of Luc(chesi), Fady, Louis Giraud and Asbotte, they testify to the rise of a playful, popular modernity, obscured by the works of potters who, like Capron, Picault and others, achieved an international notoriety at their expense; masking their significant contributions to the Vallauris ceramic renaissance.

|

| Engraved mark 'VALLAURIS' on base; but very probably Le Vaucour. |

Door to Study Collection.

Display case 12

Bauhaus

This display presents modernity as a succession of actions and modifications of previous forms — in this instance from Neo-classicism — designed for serial production in undecorated porcelain.

Above (left to right)

Above (left to right)

58. Carl Friedrich Schinkel,

‘Fidibus’ vase (1820-30), edited by KPM, Berlin.

This represents the Neo-Classical nucleus from which the Halle vase was evolved. The onion shape was derived from Ancien Greek Attic vases and was widely used in ceramics, and for making concrete and cast iron urns for use in parks.

59. Marguerite

Friedlaender-Vildehain, Halle vase (1931), KPM.

Morphologically, the form of the Halle vase was evolved by pulling the Fidibus vase upwards; to extend it dynamically along a vertical axis.

60. Marguerite Friedlaender-Vildehain, Small Halle vase/tea caddy (1931),

KPM.

61. Walter Nitszche, Vase for Furstenberg, 1937.

61. Walter Nitszche, Vase for Furstenberg, 1937.

Whereas an upward mouvement animates the Halle vase, here the emphasis on the body of the vase confers upon it an overall sense of stability.

This vase distills ancient forms, which it renders in simplified lines, with no surface decoration. Classical modernism?

63*-64*. Theodor Bogler, Two slipcast earthenware vases, decorated with a pitted blue glaze. For Maria Laach Abbey ceramic workshop. (1950s).

The simple, unbroken lines of the two vases and the subtle luminosity of their glaze confer upon these vases a meditative quality.

The simple, unbroken lines of the two vases and the subtle luminosity of their glaze confer upon these vases a meditative quality.

Below

65. Ursula Fesca, Jug-vase.

Slip-cast stoneware decorated with ‘Oslo’ ‘dekor’. c.1950.

66-67. Ursula Fesca, Two jug-vases. Right: design:

1930s. Glaze: c. 1950. For Wächtersbacher. Left: design and glaze: 1950s.

This juxtapposition (different from the one in the exhibition) of two jugs of very different design that may have been edited around the same time (1950s; after Fesca's return to work at Wächtersbacher) illustrates the co-existence of old (Bauhaus) and new (Streamline) forms at a time when a key stylistic change was about to take place in Germany.

68. Cedric Ragot, 'Fast' vase, for Rosenthal. Porcelain. 2004.

On one side 'Fast' emulates classical Chinese forms:

On one side 'Fast' emulates classical Chinese forms:

On the other side, it reveals a disquieting feature, as its surface is pulled by an invisible force:

Ragot interpreted this spectacular disruption of the surface of the vase as an expression of the digital age.

Case 13

Stoneware revival.

Top

69. Ichino Shinsui (1932-2001). Second generation of Shinsui kiln. Vase for tea ceremony. Tamba ware. Hand-thrown, then reshaped, stoneware. 1960s.

It is not known exactly when this vase of Tamba ware made its way to Germany, probably during one of several exhibitions* during the 70s that made the German public more aware of Japanese stoneware. The Kubicek vase in the same case (and the two illustrated below) shows that German potters were aware of Japanese stoneware and were assimilating its influence. Some artists like Rudi Stahl and Gerhard Liebenthron combined Japanese influences with the local (Westerwald) German tradition of undecorated stoneware in some of their work.

*See, for instance the catalogue of Japanische Keramik, Kunstwerke historischer Epochen und der Gegenwart (1978) of the exhibition that was shown in Dusseldorf, Berlin and Stuttgart.

70. Elmar and Elke Kubicek, Vase [right]. Hand-thrown stoneware decorated in brown and yellow semi-crystalline glaze. c. 1960.

Of these three vases by the Kubicek, only one is included in the exhibition (right). The group, however, shows how they assimilated Japanese forms from ceramics for the tea ceremony: sake bottles, vases, etc.

71. Tea bowl. Japan.

The storage box is inscribed: ‘narumi yaki aka-shino tutu-cha-wa' [red shino cylindrical teabow]

'Narumi-Yaki, 16th century. Narumi-Town, Nagoya-city, Aichi-Prefecture'.

72-73. Ilka Schilbock. Two ‘krug vases’. [‘A pot of paint flung in the face of German stoneware’]. Hand-thrown stoneware.

1970s.

The simplified lines of the two bottle-vases up-date and refine two traditional forms of German domestic vessels. The uncompromising application of the luscious blue glaze instigates a new modernity through a free interpretation of the traditional blue glaze in a tachiste vein. Hence the (ironic) title I have given to the vase… echoing the Ruskin vs Whistler trial…

Below

74. Royal Lancastrian. Vase. Slipcast earthenware decorated with a version of the famous ‘orange vermilion’ uranium glaze. 1930s.

Unlike the hand-thrown vase displayed in case 6, this one was slip-cast and decorated with the more dramatic and famous 'orange vermilion' glaze; one of the pride glazes developped at the Royal Lancastrian works, from uranium oxides.

This type of glaze, which relied on extensive knowledge of and engagement with glaze chemistry, stands out alongside the works of William Howson Taylor, at the Ruskin Pottery, and prefigures in Britain the subsequent experiments that, from the 50s onwards, in France, Germany and Italy, promoted color and texture as key attributes of a new aesthetics.

In Britain, the exponents of this trends (inspired by Dalpayrat's work seen at the 1900 Paris International Exhibition) were derided as mere 'glaze chemist' by Leach and the exponents of the studio pottery revival.

Rather than assuming with Bernard Leach and others that factory production is incompatible with artistic quality, this exhibition identifies concrete examples in which the integration of art and craft skills within industrial or semi-industrial production enabled team work to achieve works of real artistic quality.

75. Wilhelm Kagel, Two-handled jug. Hand-thrown earthenware decorated with sgraffito under green glaze.

The invention of (a new) Tradition…

Departing from the conventional floral decoration adopted by his father, William Kagel evolved a subtle neo-traditional style based on fine sgraffito patterns on earthenware vessels uniformly coated with a single matt glaze: green, yellow, orange or blue. The result has a distinctive Art and Craft feel, with a subtle touch of modernity.

Departing from the conventional floral decoration adopted by his father, William Kagel evolved a subtle neo-traditional style based on fine sgraffito patterns on earthenware vessels uniformly coated with a single matt glaze: green, yellow, orange or blue. The result has a distinctive Art and Craft feel, with a subtle touch of modernity.

Top

76. Veb

Haldensleben, Slipcast vase decorated with a blue and white snake glaze (below left). 1970s.

77-79. Studio Unterstab. Three hand-thrown

stoneware vases decorated with a blue crystalline glaze. 1970s:

80. Wendelin Stahl. Hand-thrown stoneware vase decorated with blue crystalline glaze. 1970s.

Middle

81. Albert Kiessling, Vase. Hand-thrown stoneware, decorated with white snake glaze

(1960s).

Close examination of the glaze shows the formation of 'scales' ; the first step towards the development of 'snake glazes'.

The following three vases, by Albert Kiessling, shows two different ways of achieving snake glazes; by breaking the continuity of the glaze surface in a 'crazy paving' type pattern or by creating a cluster of raised glaze nuggets using a wax resist process:

83*. Hand-thrown stoneware vase decorated with green and white snake glaze (on stand). 1960s.

84-86. Studio Unterstab. Three hand-thrown stoneware vases decorated with snake glazes. 1970s:

The similarity between some of the glazes used by the Unterstabs and by Albert Kiessling may be accounted for by the continuity from one studio to the next. In the absence of secure dates, the glaze on this vase that bear the Unterstab mark may have been produced after Kiessling's death in 1964.

This is particularly evident in the blue and white glazes that recently appeared on the market (not in the exhibition):

Bottom

87. Scheurich, Vase (529/25), slip-cast stoneware, decorated with dark green, variegated lava glaze.

88. E.S. Keramik, Krug vase decorated with dark

blue and white on black lava glazes.

89. Fohr Keramik, Slipcast vase (513/25) decorated with

shiny red on matt black lava glaze (below, left).

Here the slipcast Fohr vase meets a hand-thrown vase by Annette Roux from Golfe Juan (near Vallauris). The encounter highlights the contrast between the subjective, free-flowing, painterly motif on the Vallauris (right) and the objective form (but aleatoric) chemistry of the lava glaze on the German vase.

90*. Fohr Keramik, Slipcast stoneware vase (411/20), decorated

with matt black pumice on yellow shiny glaze, with black occlusions. 1970s.

Here, by contrast, the application of the black pumice glaze required a different mastery, on the part of the glazier, to control the flow of the black glaze and ensure that it did not run too far beyond the shoulder of the vase.

Case 15

Lava Glazes

This juxtapposition, inspired by Gulliver's Travels, presents a visual proposition about organic forms in ceramics. Whereas the motif of the gourde was used by Edwin Martin in stylised (non-literal) decorative ways, in the Kreutz vase, the surface treatment reaches into the fabric of the vase, emulating the organic look of a rotting fruit; combining it with a mineral (and industrial) references to volcanic lava.

92. Scheurich Large vase (517/30), decorated with a purple blue irrisdescent lava glaze.

The contrast between the restrained, classical symmetry of the vase and the experimental lava glaze produces a quirky example of ceramic post-modernity that uses tradition as a basis for innovation.

93. Jopeko/Stein,

Krug vase. Slipcast stoneware decorated with dark green and black running on

bright yellow glaze.

The classical form of the jug, also available in a plain green glaze, is enhanced by the addition of a dark green streak of glaze running down its neck.

Besides blurring the regular, classical form of the jug, the glaze injects it with a sense of dynamism that arises from its spectacular materiality and brightness.

95-96. Conversation (left): Rudi Stahl. Hand-thrown, unglazed stoneware vase (1950-60s) . Scheurich. Slipcast round stoneware vase decorated with red and black lava glaze (1970s).

The heavily grogged, hand-thrown, unglazed stoneware vase by Rudy Stahl (left) exhudes a timeless beauty, and a synthesis of East and West that remove rustic elements; avoiding oriental pastiche.

The subtle ascending curves of the vase and its raw unadorned (ascetic) body confer upon it the Zen quality of an abstract sculpture — Brancusi-like — of simple metaphysical resonance.

By contrast, the regular (moulded) contour of the Scheurich vase (form '284/19') is blurred and enhanced by the thick lava glaze, which brings it to life; placing its outline in a state of flux; as if it could melt and loose its form at any moment. Allusion/celebration of the fire that melted its surface?

The juxtapposition of these two aesthetically very different vases creates a tension and a polarity. The point, here, is not to emphasise that one was made in a studio and the other in a factory, but to highlight that, through their distinct materialities and form/design qualities, and through their respective modes of production, they each express a distinct aesthetics, which, in this juxtaposition, can trigger a spiritual dialogue, transcending their function as vases.

|

Case 16

In this encounter, a serially-produced, but hand-thrown, stoneware bottle vase by Rudi Stahl (left) inspired by a traditional country form faces a slip-cast vase designed by Kurt Tschörner (form) and Otto Gerhaz (glaze) or Gerda Heuckeroth; and made by skilful craftsmen and/or women as part of a process of collective authoring, which capitalised on the integration of craft skills in an industrial mode of production.

* acquired for the permanent collec tion.

102. Dumler und Breiden, Krug vase. Slipcast stoneware decorated with white lava glaze on matt blue glaze. Early 1970s.

103. Ü-Keramik. Large chimney vase (1447/45). Slipcast stoneware decorated with white and cream running on dark blue glaze.

Case 17.

Above

(Information Courtesy Ralf Schumann)

Middle

110-115. Roth Keramik. Selection of 6 vases decorated with a black pumice glaze over a bright red or an orange glossy glaze.

The processes involved here are virtually identical, with minor variations.

Bottom

116-120. Marei Keramik. Selection of 5 vases, decorated with lava glazes.

The matt black on glossy red glaze on the vase on the right, called 'lava', seems to have been introduced in Spring 1967 (info courtesy Ralf Schumann). The Marei vases shows a more varied and more complex range of glazes than the Roth; although until recently they were believed to have been made at the Roth factory.

The matt black on glossy red glaze on the vase on the right, called 'lava', seems to have been introduced in Spring 1967 (info courtesy Ralf Schumann). The Marei vases shows a more varied and more complex range of glazes than the Roth; although until recently they were believed to have been made at the Roth factory.

121-129. Charles

Cart. Le Cyclope pottery (Annecy, France).

Selection

of 9 decorative earthenware vessels decorated in the ‘Émaux des glaciers, émaux des neiges’

(blue and white on black) and ‘Émaux des guarrigues’ (honey yellow) glaze.

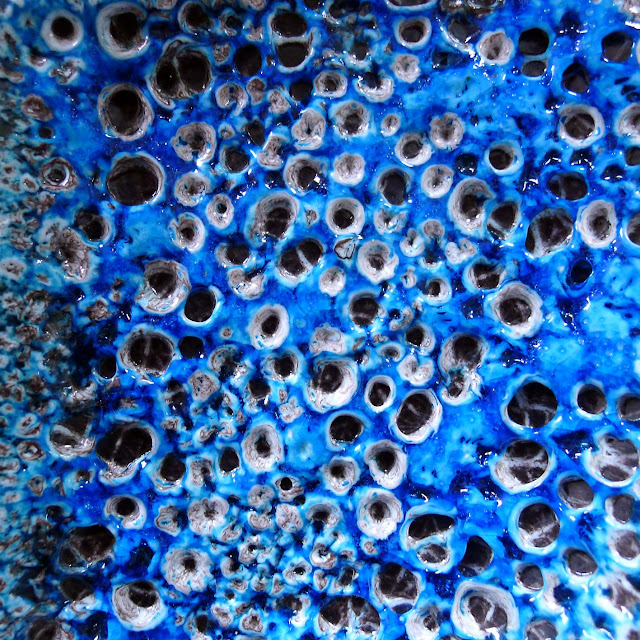

The close up photo of the fondue or tapas plate, below well illustrates Charles Cart's deconstructive approach to glazing.

For his research Cart asked chemist to show him how to 'spoil' glazes. The result produced his outstanding glazes which seem to have been inspired by the famous Vallauris's 'Écume de Mer' glaze, for which he (or retailers) used the label on some of his early production; including the vase above.

Cart (if he did put the labels) probably did it to capitalise on the popularity of the 'écume de mer' glaze before establishing his own reputation with 'Émaux des glaciers. Émaux des neiges', 'Émaux des garrigues' and 'Émaux Terre de Feu'.

As was customary at the time, paper labels were often added, which suggested that the works (made in Annecy) were in some way connected with the places where they were sold. One Cyclope jug, recently bought in Pyrénees Orientales, still carried the paper label 'Emaux des Pyrénées'! Clearly a ploy to suggest that the piece was made in the area where it was sold; to better qualify as a tourist 'souvenir' from the region!